|

| Mentor/New American Library 1977, Art: Paul Stinson(?) |

As a young teenage reader interested in science fiction in the 1970s, the promise of books like James Gunn's The Road to Science Fiction always appealed to me. Logically speaking, if I could understand how sf developed from its earliest forms, then I could more fully appreciate it in its current form(s). In other words, I hoped that this series would act as a self-teaching aid so that I could have a broader appreciation of some of the "new wave" stuff that was coming out at that time. However, one does not simply walk into the literary worlds of Sir Thomas More and Francis Bacon after having just shelved Star Wars, Conan and Robert A. Heinlein's juvenile-oriented science fiction novels (Red Planet, Have Spacesuit - Will Travel, etc.). Although the covers of the books in the series inspired me to buy all three volumes (later expanded to six), when I actually attempted to read these things it was...torturous. I think I gave up on Volume 1 pretty early on and then just decided to skip ahead to Volume 2. I think I may have read the introduction to Volume 3. Not only that, but Gunn's introductory notes were heavy on the academic theory and light on fun. It's possible that I might have actually managed to get through more of Gunn's series if not for my discovery of the books of Michael Moorcock and Roger Zelazny, whose ironic writing styles were completely in line with what I was looking for in science fiction and fantasy at that time.

Now, dozens of years later, with more patience and a much more rounded view of world history, I can much better appreciate what Gunn was doing in his series. I posted a guide to Volume Two earlier, and my enjoyment of that book gave me the courage to plunge deeper into the misty past. Anyways...

Introduction (Gilgamesh and Greek Mythology)

A True Story (Lucian of Samosata, 185 AD)

The Voyages and Travels of Sir John Mandeville (Anonymous, 14th century)

Utopia (Sir Thomas More, 1516)

The City of the Sun (Tommaso Campanella, 1602)

The New Atlantis (Francis Bacon, 1627)

Somnium, or Lunar Astronomy (Johannes Kepler, 1610)

A Voyage to the Moon (Cyrano de Bergerac, 1657)

Gulliver's Travels: "A Voyage to Laputa" (Jonathan Swift, 1726)

The Journey to the World Underground (Ludvig Holberg, 1741)

Frankenstein (or, The Modern Prometheus) (Mary Shelley, 1818)

"Rappaccini's Daughter" (Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1844)

"Mellonta Tauta" (Edgar Allan Poe, 1849)

"The Diamond Lens" (Fitz-James O'Brien, 1858)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Jules Verne, 1870)

Around the Moon (Jules Verne, 1870)

She (H. Rider Haggard, 1886)

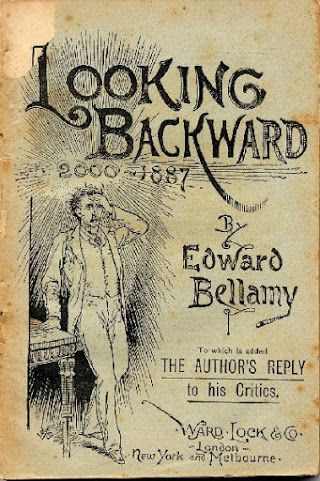

"Looking Backward, 2000-1887" (Edward Bellamy, 1888)

"The Damned Thing" (Ambrose Bierce, 1893)

"With the Night Mail" (Rudyard Kipling, 1905)

"The Star" (H. G. Wells, 1897)

As the story goes, in the 1970s writer James Gunn began teaching a

course on science fiction. His classroom lecture notes were apparently later

used to annotate a series of anthologies titled

The Road To Science Fiction. The first volume in the

series is subtitled "From Gilgamesh to Wells" and covers the development of

science fiction from the very first written epic (the Mesopotamian epic

Gilgamesh) to the late 19th century works of H.G. Wells. The next few

paragraphs summarize the entire book and highlight the examples included in it, situating them in the context of Gunn's chronology of early science-fiction.

From the beginning, the earliest historical epics already described fantastic beings with great powers who frequently traveled to exotic lands (Gilgamesh, Greek mythology). In Roman times, the writer Lucian of Samosata first proposed a journey to the moon (A True Story), a concept which would remain popular for almost the next two millennia. This lunar obsession would later be picked up writers like Johannes Kepler (Somnium, or Lunar Astronomy) and Cyrano de Bergerac (A Voyage To the Moon).

However, descriptions of strange and exotic Earth-bound locales were also used

in many “tall tales” such as

The Voyages and Travels of Sir John Mandeville. These travelogues were

eventually used to make social statements proposing improvements to current

political and social systems. These far away “utopias” (and some satirical

“anti-utopias”) were described by writers like Sir Thomas More

(Utopia), Tommaso Campanella (The City of the Sun), Francis

Bacon (The New Atlantis) and Jonathan Swift (Gulliver’s Travels).

In the 18th century, technology had advanced to the point that

exotic scientific theories could become the entire focus of a story (even

without an underlying socio-political message). This kind of early science

fiction was pioneered by writers such as Ludvig Holberg (The Journey of Niels Klim to the World Underground), Mary Shelley (Frankenstein) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (“Rappaccini’s

Daughter”).

In the 19th century, writers began to imagine possible

futures for the first time (that is, futures which were fantastically

different than their own times). These writers included Edgar Allan Poe

(“Mellonta Tauta”) and Edward Bellamy (Looking Backward). This kind of

speculation would eventually find modern maturity in Rudyard Kipling’s “With

the Night Mail (A Story of 2000 AD)”, in which the viewpoint (and vocabulary

used) is entirely that of a citizen of the future. Science fiction in the 19th

century also centered around fantastical “lost worlds” (hidden sanctuaries

which allowed pocket civilizations to develop independently from European

ones). Sometimes these could be found in unexplored jungles (H. Rider

Haggard’s She) and some could even be found in microscopic universes

(Fitz-James O’Brien’s “The Diamond Lens”).

From a commercial

standpoint, Jules Verne helped raise science fiction’s profile with his

immensely popular “extraordinary voyages” (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the Moon, etc). Science fiction also grew in psychological complexity due to writers

like Ambrose Bierce, who explored (amongst many other things) the “invisible monster” concept (“The Damned

Thing”). Finally, H.G. Wells created highly influential models for 20th century science

fiction with his many novels exploring subjects such

as time travel, genetic mutation, alien invasion, invisibility, space travel

and cosmic Armageddon (“The Star”).

Below are synopses of each of the stories included in Volume 1 of Gunn's history of science fiction, preceded by summaries of his introductory notes to each one (I included one or two of Gunn's most concise passages in quoted paragraphs).

|

| Story of "Gilgamesh and Agga" (2003-1595 BCE). Old Babylonian period, from southern Iraq. Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq |

Introduction (Gilgamesh)

Science fiction is concerned with

mankind’s reaction to new technology and new discoveries. At its core is a new

“idea”. In order to reach an socio-technological state in which science

fiction could even be conceived, writers first had to reach a point where they

could characterize mankind as a single race, not separated by nationalistic or

political divisions. Additionally, they needed to be able to express

skepticism of religion, conceive of a future different than their present

state of affairs, and be exposed to new technologies. However, even the

characters of the earliest written epic, Gilgamesh, demonstrated human

aspirations which would eventually surface in mature science fiction: to control his

environment, to control others, to live forever, to protect his culture and

family. In the beginning, these dreams were realized through god-like heroes.

Gilgamesh synopsis (Gunn):

“Gilgamesh was part god—the son of a goddess and a high priest—who became king

of Uruk. But his exuberance, strength, vigor, and arrogance led him to carry

off the maidens and force the young men to work on the city walls and the

temple. Finally, his subjects called on the gods for relief. They responded by

creating a wild man of incredible strength named Enkidu. Eventually, led by a

prostitute, Enkidu came to battle Gilgamesh; after a terrific fight, Gilgamesh

was victorious and the two became friends. They went off together to win fame

by killing a terrible ogre who guarded a vast cedar forest. With the help of

the gods, they succeeded. On their return to Uruk, Ishtar, goddess of love,

offered to be Gilgamesh’s wife, but he refused. Enraged, she asked her father,

Anu, to send the bull of heaven to destroy Gilgamesh, but Enkidu and Gilgamesh

killed the bull. The gods decided that one of them had to die; Enkidu was

chosen by lot. Torn by grief at the death of his friend, stricken by the

thought that he, too, must die, Gilgamesh went to seek immortality from

Utnapishtim, the Babylonian Noah, who was made immortal by the gods. After

great difficulties and perils, Gilgamesh finally reached Utnapishtim but

learned that only the gods can confer immortality, and why should they choose

him? One hope remained: a thorny plant that grew at the bottom of the sea

could rejuvenate old men. Gilgamesh retrieved some, but on his return home, as

he was bathing, a serpent ate the plant (and thereby won the power to shed its

skin and renew its life). Gilgamesh wept, but eventually he returned to Uruk,

having learned to be content with his lot and to rejoice in the work of his

hands.”

Another early myth which points towards some of the

elements of science fiction is the Greek story of Daedalus and Icarus.

Daedalus and Icarus synopsis (Gunn):

“Technology plays a more significant part in the Greek myth of Daedalus, a

craftsman said to have been taught his art by Athene herself. He took as

apprentice his nephew Talos and then killed the boy out of jealousy when he

invented the saw, the potter’s wheel, and the compass. Daedalus had to flee

from Athens and went eventually to Crete. King Minos welcomed him to Knossos.

There Daedalus fathered Icarus, built the maze called the labyrinth for the

bull-headed man called the Minotaur (the result of the unnatural coupling of

Pasiphaé and Zeus’s white bull), and perhaps constructed the bull-headed

bronze servant (the first robot?), also named Talos, who ran three times a day

around the island of Crete, threw rocks at any foreign ships, and destroyed an

army of invading Sardinians by turning himself red-hot in a fire and

destroying them with his embrace (other versions say that Talos was a survivor

of the bronze race of men who sprang from the ash trees, or that he was forged

by Hephaestus in Sardinia and given to Minos by Zeus). Minos finally learned

that his wife’s coupling with the white bull had been made possible by

Daedalus, who constructed for Pasiphaé a hollow wooden cow in which she placed

herself. Minos locked Daedalus and Icarus in the labyrinth; Pasiphaé freed

them, and Daedalus fashioned wings out of feathers and wax. The escape,

however, ended with Icarus ignoring his father’s warning, flying too near the

sun, and plunging into the sea (later named the Icaran sea in his honor) when

his wings melted. The basic story contains many of the elements of later

science fiction: the inventor imprisoned in his own invention, escaping

through his ingenuity, and losing someone close to him because of the

incautious use of the new technology.”

Homer’s epic poem

The Odyssey also had elements of what could be considered science

fiction today. It describes a journey in which the hero encounters many

strange objects and beings. Plato’s works Timaeus and

Critias described Poseidon’s creation of Atlantis, a semi-mythical city,

as well as its eventual destruction by the angry gods. Both the

Bible and Greek mythology incorporated a “Golden Age” into their origin mythologies.

In the Bible this is known as the Garden of Eden, whereas in Greek myth the

"Golden Age" is a period in which perfect beings roam (but which are later

replaced by the inferior savages of the harsh "Iron Age"). In contrast

to these “falling” states, Plato’s Republic described a possible "utopia"

of the future. Early Greek satire also hinted at one or two science fiction

elements to come. For example, in Aristophanes’ The Clouds Socrates hangs in

a "sky basket", and in Aristophanes’ The Birds the Athenians have birds build a

"sky wall" to halt sacrifices to the gods.

|

| Art: William Strang, 1894 |

A True Story (opening excerpt) synopsis: Lucian announces from the outset that he is going to relate a “tall tale”, just as other writers such as Homer have done in the past. He reports that he and his crew had sailed into the Atlantic and after braving a great storm had discovered an island of carnivorous sex-plants. After escaping this nefarious island, his ship is caught in a great wind and blown skyward, and eventually lands on the surface of the moon. There, they meet another repatriated Earthman named Endymion, who is leading the “moonmen” in a war against the “sunmen” (led by their king Phaethon). When Endymion’s giant spiders spin a web connecting the moon with the Morningstar (Venus) in order to colonize it, his forces are soon engaged by the sunmen’s opposing army in a heavenly battle. Each of the armies employ soldiers and hybrid cavalry mounts created from fruits, vegetables and animals. The moonmen are eventually defeated and the sunmen create a cloud barrier between the Earth and the moon, putting the moon into bleak darkness. A treaty is then signed where the moonmen give fealty to the sunmen and both agree to colonize the Morningstar on equal terms. After describing the strange sex lives of the moonmen, Lucian’s ship departs from the moon surface and then visits a sky city populated by lamp-people (one of which is his own lamp from his Roman home). Afterwards, Lucian and his crew visit Cloudcuckooland (and references Aristophanes’ The Clouds). Eventually, they land back on Earth and continue their journey on the sea.

2. The Voyages and Travels of Sir John Mandeville (excerpt) (Anonymous, 14th C.)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "Strange Creatures and Far Traveling")

After Rome falls, fantastic literature in

Europe survived in the form of oral epics:

- 8th C: Beowulf

- 12th C.: The Nibelungenlied, Arthurian romances (by the poet Chrétien de Troyes), and Parzival (Wolfram von Eschenbach) which describes Sir Percival’s chivalric search for Arthur and the Holy Grail.)

- 1321: Dante’s Inferno (The Divine Comedy) (analyzed HERE).

- 14th C.: Bocaccio’s Tales, Decameron (various tales of fanciful nature)

- 1357-71: The Voyages and Travels of Sir John Mandeville (Anonymous, probably a collection of various tales)

At the same time the Middle East produced

One Thousand and One Nights (The Arabian Nights), which would later be

reborn as stories involving Ali Baba, Aladdin, Sindbad, flying carpets, rocs,

etc.

The Voyages and Travels of Sir John Mandeville (Ch. 18

& 19) synopsis:

The English knight Sir John Mandeville journeys around the world. In this

excerpt he describes the islands and peoples of South Asia (Java), who are

either wealthy nobles, primitive savages or bizarre fanatics. Some live in giant

snail shells, while others engage in cannibalism and/or fight dragons. He also

describes a race of people who have dog heads, and another who have eyes in

their shoulders.

Full text on Project Gutenberg

3. Utopia (excerpt) (Thomas More, 1516)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "The Good Place That Is No Place")

In 1294 (while jailed for anti-Church sentiments promoting scientific

thought), the Franciscan friar Roger Bacon wrote a letter in which he

predicted engine-powered ships, planes, submarines and cars of the future.

Elements of the fantastic and the supernatural also surfaced at the end of the

Middle Ages in works such as Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (1387) and Malory’s

Morte d’Arthur (1469).

In 1492, Columbus discovered America, and these

undiscovered lands soon became the locales of even more fantastic literature.

In 1516, the scholar Sir Thomas More wrote Utopia, which described an island

“no-place” which had all the features of a political paradise. Other utopian

works to follow will include Campanella’s The City of the Sun (1623), Francis

Bacon’s The New Atlantis (1624), and Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels

(1726).

Even later, an opposite reaction to this “good” utopia will

appear in the form of “anti-utopias” (dystopias, “bad places”) in books like

Butler’s Erewhon (1872), Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888), Wells’ The New

Utopia, etc.

Utopia (excerpt from Bk II) synopsis : A sailor

named Raphael describes (to Sir Thomas) a “Utopia” (“no place”) on a distant

island where the political system (a “commonwealth”) is much fairer than any

other found on Earth. There is no rich and no poor, and everyone is treated

with respect. Raphael wishes that the greedy men of his homeland could be

removed so that this much fairer system could be instituted.

4. The City of the Sun (excerpt) (Tommaso Campanella, 1602)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "The New Science and the Old Religion")

In 1517 Martin Luther instigated the Protestant Reformation, which

eventually allowed the birth of new technologies in astronomy, map-making, mineralogy, firearms, microscopic research, and mathematics.

In 1532,

Ludovico Ariosto wrote Orlando Furioso, an epic poem where the

character Astolpho journeys to the moon in search of his friend Orlando’s lost

wits (the moon is rumored to hold everything that has ever been lost on

Earth).

Written in 1605, Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote is

considered the first novel and, from a science-fictional viewpoint, it

presented realistic implications of living in a fantasy world.

In 1602,

Tommaso Campanella (another imprisoned monk philosopher critical of current

social affairs) wrote another utopian novel,

The City of the Sun.

The City of the Sun (excerpt) synopsis:

A sea captain describes his visit to a utopian land named Taprobane. This

“city of the sun”, settled by refugees from India, celebrates architecture,

mathematics, biology, zoology, art and all natural sciences. They equate the

sun as a father God and the Earth as a mother figure. All men are treated with

fellowship and love.

5. The New Atlantis (Francis Bacon, 1627)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "Experience, Experiment, and the Battle for Men’s Minds")

Francis Bacon (another fallen political figure) promoted the idea of

empiricism, or science based on experimental results. For this, he is known as

the father of the scientific method. In 1627 he wrote The New Atlantis,

about an island which bases its knowledge on empirical research results.

Through his efforts, the Philosophical Society was eventually formed as a

scientific organization, and in 1662 became the still-existing Royal

Society.

The New Atlantis synopsis: After surviving through a great storm, the narrator and his crew discover a utopian island society. This

island is apparently blessed by God (as signified by a glowing pillar of

light), and the inhabitants secretly obtain knowledge from other nations through secret agents

(they do not reveal their own existence to the outside world). The people of New Atlantis maintain

laboratories both deep in the ground and high in the sky, where they develop

advanced technology in the fields of medicine, physics, genetics, sound, math,

optics, etc. Their main research facility (“foundation”) is named Salomon’s

House, in respect to the Biblical Solomon, King of the Jews. Once the research

is complete, the scientists decide what secrets may be distributed to the

public. At the end of the story, the king permits the narrator to spread the

news of this secret island to the outside world.

6. Somnium, or Lunar Astronomy (Johannes Kepler, 1610)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "A New Look at the Heavens and Another Trip to the Moon")

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler

established that the Earth orbited the Sun. In 1610, Johannes Kepler also wrote

Somnium, or Lunar Astronomy, which contained the first serious (as

opposed to satirical) scientific attempt at describing a lunar landscape.

Somnium, or Lunar Astronomy synopsis:

Kepler has a dream in which he discovers a strange book. In the book, an Icelandic boy named

Duracotus is (unintentionally) sent abroad by his mother and ends up studying with the Danish

scientist Tycho Brahe. When Duracotus returns, his mother decides to teach him of

the Icelanders' special relationship to the northern spirits. She summonses a

demon, who explains to him how they are able to transport humans back and

forth from Levania (the moon). Duracotus learns that the demons can only

thrive at night or during a solar eclipse. There are two kinds of inhabitants

on the Moon, the Subvolvans (who view Earth, or Volva, as their own moon) and

the Privolvans (who live on the far side of the moon and never see the Earth).

Both grow to monstrous sizes and have short lives. Kepler eventually wakes up,

leaving the book unfinished.

|

| (art ca. 1708) |

7. A Voyage to the Moon (excerpt) (Cyrano de Bergerac, 1657)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "Commuting to the Moon")

In the 17th C., the moon seemed more attainable than ever due to the

availability of more powerful telescopes, and inspired even more moon-related

stories. In 1638, Francis Godwin wrote The Man in the Moone, in which

swan-like birds called “gansas” accidentally pull the protagonist’s chariot to

the moon, which is populated by a utopian society. In 1657, Cyrano de

Bergerac wrote his own moon-story, A Voyage to the Moon (Voyage dans la

Lune, or L’Autre monde ou les états et empires de la Lune).

A Voyage to the Moon (excerpt) synopsis: In

this satire, Cyrano captures dew in glasses attached to his body. When the sun

pulls the dew up towards the heavens, it carries de Bergerac into the air as well. After a

crash landing in French Canada, he decides to use the lighter-than-air

properties of bone-marrow for another attempt. In the meantime, soldiers

capture his vehicle and attach fireworks to it for entertainment purposes.

Cyrano leaps on board but the fireworks are set off and drive him and his

carriage into space. After landing on the moon, he discovers the biblical Tree

of Life (Knowledge).

In 1662 de Bergerac also wrote

Voyage to the Sun, in which he relates how he escaped from prison by

focusing the sun’s rays into a box to create a whirlwind. Carried into the

sky, he reaches the sun where he then meets a race of birds living in another

utopian society.

Wiki Entry

Other notable books containing a journey to the

moon (leading up to mankind’s actual first moon landing in 1969) include

Gabriel Daniel’s A Voyage to the World of Cartesius (1691), Ralph

Morris’ John Daniel (1751),Aratus’ A Voyage to the Moon (1793),

George Fowler’s A Flight to the Moon (1813), George Tucker’s

A Voyage to the Moon (1827), Edgar Allan Poe’s

Hans Pfaall (1840), Jules Verne’s

From the Earth to the Moon (1865), H. G. Wells’s

The First Men in the Moon (1901), and Robert A. Heinlein’s

The Man Who Sold the Moon (1950).

8. Gulliver’s Travels (excerpt from “A Voyage to Laputa”) (Jonathan Swift, 1726)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "The Age of Reason and the Voice of Dissent")

Scientific knowledge continued to grow in the 17th and 18th centuries.

In 1687 Isaac Newton published his breakthrough scientific text

Principia Mathematica, which eventually ushered in the “Age of Reason”. However, this rise in

scientific thought also became a target of opposition in the form of satire.

In 1726 Jonathan Swift wrote Gulliver’s Travels, a satire which

attacked, among other things, religion, politics, humanity and the new trend towards scientific research. There are four stories in

Gulliver’s Travels:

- Voyage to Lilliput: Gulliver meets tiny people who at first seem to be admirably brave are later revealed to be as petty as their stature.

- Brobdingnag: Gulliver encounter giants who at first seem gross and undisciplned, but are later revealed to be a generous and enlightened people.

- Laputa: Gulliver visits a flying city where society is organized around science at the cost of their humanity. In this tale he directly criticizes the empirically-based research pioneered by Francis Bacon and the Royal Society he founded.

- Houyhnhnms: Gulliver meets the Houyhnhnms who appear to be so superior to Gulliver and his countrymen that Gulliver must declare even himself to be an inferior “Yahoo” (Swift did not believe that man was inherently good).

“A Voyage to Laputa” (excerpt) synopsis:

- Swift is invited on an ocean journey by an old friend. Unfortunately his sloop is raided by pirates and Swift is forced to cast off alone in a canoe. Wandering amongst uninhabited islands, he spots a floating city and soon asks them for aid.

- Swift is drawn up to the island on a chair held on strings. On the island (named Laputa), he encounters a strange people who are only concerned with mathematics and music. They are unable to enjoy life because they are constantly worried about the destruction of the Earth due to possible astronomical phenomena. They also ignore their women, who often try to escape the floating island to live amongst the land people.

- Laputa is held aloft by a gigantic magnetic lodestone at its center, which is manipulated so that it alternately repels or is attracted to the magnetic elements of Earth below it. By angling the lodestone, the island can be made to float in various directions. When a land-based kingdom needs to be disciplined, the king of Laputa can threaten to crush it (by landing Laputa on it). However, this tactic was once foiled when the city of Lindalino erected piercing, magnetic towers which would have caused Laputa to crack in half had it tried to land on top of the city.

- Swift becomes bored with the obsessed mathematicians of Laputa and so asks to be returned to the surface of the Earth. He is dropped off at the city of Lagado and introduced there. In Lagado, Swift discovers that the city is in disrepair because the scientists (influenced by the scientists of Laputa) are constantly trying to improve productivity with technology, but are never able to actually complete any projects.

- Swift is given a tour of the scientific academy, and there he meets several scientists ("projectors") who are engaged in various unfeasible experiments (such as the conversion of excrement to food, the elimination of spoken language through a physical inventory of display objects, and the teaching of math by swallowing wafers inscribed with information.

- Swift meets more scientists in the field of social science, who propose various impractical ideas in order to conduct government and select new appointees to city positions. Swift suggests his own obviously outlandish ideas (deciphering secret messages through nonsense codes, etc.) and these are in turn praised.

9. The Journey of Niels Klim to the World Underground (excerpt) (Ludvig

Holberg, 1741)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "Imaginary Voyages in the Other Direction")

Many new developments (such as James Watts’ 1769 steam engine) soon led

to the Industrial Age. With the invention of the printing press, a new middle

class book consumer also appeared. In 1741, Ludvig Holberg wrote The Journey

of Niels Klim to the World Underground. This was another book aimed at social

criticism (to define "virtue and vice") but it also had a more involved story, and increased realism through its use of fictional

documentation (letters, etc.) and believable heroes.

Full synopsis (Gunn): “Niels Klim, an impoverished university graduate, seeks to make a reputation for himself by exploring a mysterious cave in Norway. He falls through the earth, orbits a central planet, and fights off a griffin. Then he is pulled by the griffin to the planet where he discovers intelligent, mobile trees who consider him so flighty and shallow that he is good for nothing but carrying messages. He tries to get a law passed to over-throw the equality of the sexes but is condemned to be flown to the “firmament” (the inside of the earth). There he encounters all kinds of civilizations of monkeys, tigers, bears, gamecocks, bass fiddles, ice creatures, and finally humans. For the humans he trains cavalry, manufactures muskets, builds ships, and leads them into battle, where he is victorious. He succeeds the emperor and subdues most of the kingdoms of the “firmament” before power corrupts him. His people rebel against his cruelty, and trying to hide, he falls back through a hole in a cave and finds himself in Norway again.”

Niels Klim Wiki Entry

In 1752, Voltaire wrote

Micromégas. This book is not excerpted in Gunn's anthology, but is an important science-fictional satire. It features an advanced alien being as its protagonist, who makes "first contact" with mankind.

Micromégas synopsis: Micromégas, a gargantuan alien from Sirius, is banished for expressing interest in insects (which are too small for Sirians to detect). At Saturn, he meets the secretary of the Academy of Saturn and they decide to visit Earth together. At first they fail to detect any life on Earth at all due to their great size (in comparison to Earth life forms), but they eventually detect a few humans and are surprised that such tiny beings are sentient. The humans try to impress the aliens with the writings of Aristotle, Descartes, Malebranche, Leibniz and Locke, but these authors only prompt laughter from the star travelers. Micromégas then leaves a book with the humans which will supposedly explain the universe to them. However, when the humans later open the book, they only find blank pages.

|

| 1831 Frontispiece |

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "Science and Literature: When Worlds Collide")

In the late 18th C. scientific exploration turned from the “hard”

sciences of astronomy and physics to the more earthbound sciences of biology,

psychology, and evolution. Mesmer also began to develop his idea of hypnosis

(“mesmerism”). In 1764, Horace Walpole wrote the first gothic novel,

The Castle of Otranto. This book featured Gothic trappings such as a frightened woman in a

medieval castle confronting supernatural horror (amongst other Gothic

elements). This was followed by another Gothic novel in 1786: William

Beckford’s Vathek.

Finally, in 1818, advances in

electricity, biology (Darwinism) and Gothic literature inspired the first true

science fiction novel, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. In 1826 Shelley

also wrote The Last Man, in which a plague kills everyone on Earth

except one man in the 21st Century (which turns out to be no different than

the world in 1826)

*** I analyzed Frankenstein HERE. ***

|

| 1880 (http://www.hawthorneinsalem.org/images/image.php?name=MMD2810) |

11. “Rappaccini’s Daughter” (Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1844)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "Science as Symbol")

In 1830, Richard Adams Locke wrote The Moon Hoax (“Discoveries In the

Moon Lately Made at the Cape of Good Hope, by Sir John Herschel”), which led

people to believe that telescopes had detected living creatures and buildings

on the moon. Famous writers such as Darwin, Tennyson and Goethe praised modern

technology, but others like William Blake and Ralph Waldo Emerson were more

hesitant about the implications of industrialization. Another one of these

skeptics was Nathaniel Hawthorne. Hawthorne became intrigued by science and

used it (mesmerism, artificial animals, immortality elixirs, etc.) in some of

his stories. However, he generally used it for its symbolic (and didactic)

value, using science to highlight a "moral choice" (just as he used Puritan values in The Scarlet Letter).

“Rappaccini’s Daughter” synopsis: A mad

scientist exposes her daughter to poisonous plants in order to make her a

poisonous being herself (and invulnerable to disease). The speaker falls in love with her and unwittingly

begins to take on poisonous characteristics himself. His friend gives the

speaker a “cure” which has the power to cure the effects of the poisonous

plant. When the girl realizes how her father has manipulated her into becoming

a poisonous creature, she drinks the cure in an act of rebellious

self-destruction.

|

| Art: Fritz Eichenberg for Tales of Edgar Allan Poe (Random House, 1944) |

12. “Mellonta Tauta” (Edgar Allan Poe, 1849)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "Anticipations of the Future")

The work of Edgar Allan Poe was later presented by publisher Hugo

Gernsback as a model for his science fiction pulp magazine Amazing Stories. He stressed the importance of scientific explanations for unusual phenomena. More importantly, Poe wrote only for an emotional effect, rather than to educate or convey a moral/political message. He created the detective story, influenced modern poetry and perfected the short story form, especially in horror and fantasy. Like others, Poe became fascinated by the possibilities suggested by mesmerism

and used this technique in some of his stories ("A Tale of the Ragged Mountains", "The Facts In the Case of Mr. Valdemar","Mesmeric Revelation"). After writing about a moon journey by balloon ("The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfall"), he accused Locke’s The

Moon Hoax of lifting ideas from his notes for a sequel. In

1833, Poe wrote “Ms. Found in a Bottle”, his first pseudo-scientific story

employing the “hollow earth” concept. Other Poe works with a science-fictional

bent include The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym and “The Thousand-and-Second

Tale of Scheherazade”, which described modern technology in the eyes of a man

of Sindbad’s time.

“Mellonta Tauta” synopsis: In the first

true story of the future, a balloonist of 1000 years in the future (2848) describes

his experiences on the balloon "Skylark", and then sends off a last message as his ship heads for a

crash. It includes satirical impressions of Poe’s own time but distorted through the

mists of time (for example, the names of cities are rough variations of their current names, and Sir Francis Bacon is referred to as "Sir Hog").

*** I analyzed more of Poe's work HERE. ***

|

| (from an Amazing Stories reprint, Dec. 1926) |

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "Expanding the Vision")

In the

late 19th century, more writers began to try including science fiction elements: Honore de Balzac used an elixir of life and metal transmutation in his Gothic stories, Herman Melville wrote about an automaton, Edward Everett Hale wrote about men going into orbit by accident while working in a brick room, and Mark Twain wrote the time travel fantasy A Connecticut

Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889). In an 1898 work he even foreshadowed the

concept of television ("From the London Times of 1904"). Another important science fiction writer of this

period was an Irish immigrant to New York, Fitz-James O’Brien. In 1858 he wrote “The Diamond Lens”, which

began a trend of micro-universe stories in the industry. In contrast to

Shelley's romanticism, Hawthorne's moralizing and Poe's irony, O’Brien employed a more "realistic" tone in his fantastic tale,

and so this could be considered the first “modern” science fiction story.

“The Diamond Lens” synopsis:

After speaking to a dead scientist named Leeuwenhoek in a séance, the speaker

learns the secret to observing the microverse. In a drop of water (on a slide)

he observes a beautiful female creature and falls in love with her. However,

she eventually withers and dies. The speaker realizes that she had died

because the water droplet had evaporated.

Full text on Project Gutenberg

Below are a few other

examples of O’Brien’s stories:

• “The Wonder-smith”:

Gypsies manufacture an army of toy soldiers to kill all the Christian children

at Christmas.

• “From Hand to Mouth”: A man sits in a

hotel room surrounded by disembodied hands and months.

•

“What Was It? A Mystery”: This may be the earliest of the

“invisible-creature” stories.

• “The Lost Room”:

The narrator finds his hotel room occupied by strangers he cannot evict.

• “How I Overcame My Gravity”: An inventor makes an

antigravity machine using a gyroscope.

14. Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea/Around the Moon (excerpts)

(Jules Verne, 1865-1870)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "The Indispensable Frenchman")

In the late 18th century, electricity replaced steam as an industrial

energy source. This inspired further technological tales. Although the

Frenchman Jules Verne is not known for not “inventing” anything

(conceptually, at least), his books made fantastic literature popular. His

explorer-heroes used technology of the future to create suspense. His writings also

became a model for Gernsback's 1926 Amazing Stories, due to his journeys' reliance on futuristic technology. Below are some of his

major science-fiction-related works.

1870: Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

1875: The Mysterious Island

** I analyzed Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea HERE. ***

|

| Art: Émile Bayard, Paris (Hetzel), circa 1870 |

Around The Moon (Ch. 17, 18) synopsis: Three members of the Baltimore Gun Club have launched themselves and their space capsule into a moon orbit. They marvel at the lunar landscape and theorize on how the craters and radiating lines on the surface were formed. Later, one of them seems to spot ruins of some kind. Although the moon is apparently now uninhabited, they theorize that it must have once been able to support a thriving civilization.

15. She (excerpt) (H. Rider Haggard, 1887)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "Lost Civilizations and Ancient Knowledge")

The

arrival of intellectualism and technology also triggered a counter interest in

primitivism as found in “lost races”. These primal social entities were used

to promote the simpler, anti-technological qualities found in human courage

and strength. Nonetheless, lost world stories eventually began to be situated

in space, inside the Earth, in an atom, in the past (Atlantis) or in other

dimensions. The most famous lost race author was H. Rider Haggard. In 1885,

King Solomon’s Mine introduced the adventurer Allan Quatermain. This was later

followed by the 1887 lost world novel She.

*** I analyzed She HERE. ***

Rider’s lost race stories were later further developed by Edgar

Rice Burroughs (in his Mars/Barsoom, Venus and Pellucidar series), A. Merritt (The Moon Pool), Arthur Conan Doyle (The Lost World, 1912), and James Hilton (Lost Horizon, 1933). The modern iteration of the lost world story can be found in heroic fantasy or alien abduction stories.

16. Looking Backward, 2000-1887 (excerpt) (Edward Bellamy, 1888)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "The New Frontier")

In the late 19th century, utopian visions were still being described in

literature, but a contrasting view later appeared in the form of “dystopias”,

or “anti-utopias”. Some notable works describing a possible utopia or dystopia

follow.

1871: Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s The Coming Race: The Vril-Ya

live in an underground utopian society, and live off of a form of electricity

called “Vril”.

1872: Samuel Butler’s Erewhon: In New Zealand, a

utopian society has gotten rid of machines, fearing that they may eventually

take over mankind.

1888: Edward Bellamy’s

Looking Backward, 2000-1887 is another satirical utopia but instead of

being situated in a “lost world”, it is an uplifting vision placed (for the first time) in the "new frontier" of the future. It revived interest in utopian thought.

Looking Backward synopsis:

A man from 1887 uses mesmerism as a cure for insomnia, but ends up

over-sleeping. He eventually wakes up 130 years in the future and discovers

that socialism has solved the world’s problems. He later finds out that he had

only dreamed that he was from 1887 and has always been a citizen of the year

2000. Wiki Entry

1899: H.G. Wells: When the Sleeper Awakes: A man wakes

up in the future but, in contrast to Bellamy’s socialist utopia, the laborers

are oppressed. This is the first example of “dystopian fiction”, but other

dystopic books would soon follow and become just as important (Forster's "The Machine Stops", Zamiatin's We, Huxley's Brave New World (1932), Orwell's 1984 (1949)).

|

| The Complete Short Stories of Ambrose Bierce (1970) |

17. “The Damned Thing” (Ambrose Bierce, 1898)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "New Magazines, New Readers, New Writers")

In 1891 the first mass-oriented magazines began publication, and only five

years later the even more “middle class” pulps arrived. Some of the writers

exploring science fiction concepts in these publications included H.G. Wells,

Jack London, Mark Twain and Ambrose Bierce. Bierce drove his narratives by

creating a sense of tension between realism and fantasy. For example, in 1898,

he wrote “The Damned Thing”, which employed realism, natural dialogue and

psychological undertones in a story featuring an invisible monster (although this concept had already been touched on in Fitz-James O'Brien's "What Was It? A Mystery" (1859) and Guy de Maupassant's "Horla" (1887)). Other science fictional Bierce stories include "A Horseman In the Sky", "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge", A Psychological Shipwreck", and 1909’s “Moxon’s Master”, which was one of the earliest robot

stories.

“The Damned Thing” analysis: An outdoors-man is

killed by an invisible creature. He theorizes that the creatures’ color is

beyond the spectrum of human visibility. Wiki Entry

|

| (http://www.forgottenfutures.com/game/ff1/night.htm) |

18. “With the Night Mail (A Story of 2000 AD)” (Rudyard Kipling, 1909)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "A Flying Start")

In the early years of the 20th century, the zeppelin became a popular

mode of futuristic travel (at least until the burning of the Hindenburg in

1937). In fact, Rudyard Kipling assumed that the zeppelin would eventually

rule the skies of the future (as opposed to airplanes). His story “With the

Night Mail (A Story of 2000 AD)” is the first story to thoroughly place its

narrative entirely in the future, with no linguistic concessions to the reader

of the “past” (throughout, it employs unfamiliar “future terminology”). Unlike

earlier utopias/dystopias, Kipling used his future setting as a backdrop, not

as an example of a particular social statement (or travelogue). This kind of

story would not appear again until John W. Campbell began editing Astounding magazine, as seen in his publication of Robert A. Heinlein’s works in 1939.

Kipling's also wrote one other science fiction story, "Easy as A.B.C." (1912).

“With the Night Mail (A Story of 2000 AD)” analysis: In the

year 2000, the narrator joins the crew of a commerce zeppelin (a part of the

Aerial Board of Control airfleet). During its journey it encounters various

other sea and airships in distress.

Full text on Project Gutenberg

|

| (https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/illustration-from-the-star-by-h-g-wells) |

19. The Star (H.G. Wells, 1897)

(Gunn's introductory notes title: "The Father of Modern Science Fiction")

Just as Verne’s works did, H.G. Wells’ popular books helped to excite

the public demand for science-fiction. Hugo Gernsback also cited Wells as one of his

models for his “scienti-fiction” magazines in the 1920s (in particular

Amazing Stories). In later years, Wells’ writings turned into a kind of

propagandist fiction designed to promote a form of socialism aimed at helping

the poor. Some of his earlier, more famous science fiction works follow.

•

1895: The Time Machine

• 1896:

The Island of Doctor Moreau

• 1897:

The Invisible Man

• 1898:

The War of the Worlds

• 1899:

When the Sleeper Awakes

• 1901:

The First Men On the Moon

• 1934:

The Shape of Things To Come

“Ideas exploded in his stories. Some he adapted from the work of others. Most

seemed original: mechanical time travel, invisibility through chemicals or by

speed, attack by extraterrestrials, specialization through biology, superman,

parallel worlds, warfare using tanks or airplanes, the atomic bomb, world

catastrophe, alien influences on human evolution, man-eating plants, celestial

bodies coming close to earth, interplanetary television, prehistoric people,

conquest by ants, attack by sea creatures... His particular concern was

evolution: perhaps human evolution isn’t over, or other creatures such as ants

or giant squids, may evolve into competitors.” (Gunn)

“The Star” synopsis:

A giant, glowing object approaches the solar system and collides with Neptune.

Humanity is fascinated by the spectacle but one mathematician calculates that

it will cause the end of the world. The object seems to be headed only for

Jupiter, but Jupiter’s gravity well causes it to change trajectory towards

Earth. It nearly misses the Earth, but its approach causes massive tidal waves

and earthquakes. Oblivious to the great loss of life on Earth, aliens on Mars

observe the episode and remark that the Earth has been mostly spared, since

the continents have not changed much in their shape.

|

| Amazing Stories, June 1926 |

See also The Road to Science Fiction #2: From Wells to Heinlein